Lindsey Hancock Warden

Forced Removal

As a teacher of both English and History, I sometimes find it challenging to make the study of history relevant to my students today. While there are always connections to be made, sometimes they can feel like a stretch to my students. When we approached our study of the Trail of Tears and American Indian removal in the spring semester, I began thinking about how forced removal still happens in communities, and even in our community, today. I knew that using a tragic example of forced removal from the past as a springboard for real events that are still happening to us and our neighbors today would be a springboard to not only engage my students in the study of American history and to make the content relevant to today's real-world problems, but also to prompt my students to think, write and speak about those real-world problems in a manner that drives compassion and future activism. In this mini-unit, my students utilize a Smithsonian website to learn about American Indian removal, and apply their thinking to contemporary, real-world problems.

Table of Contents

Lesson Background & Overview

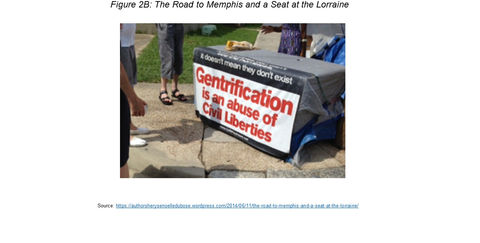

I adapted the lesson plan below from a portion of a digital, online lesson by Native Knowledge 360, an initiative by the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. To teach about American Indian Removal, I have for years utilized the digital lesson What Does It Mean to Remove a People?. My Teaching for Transformation II class challenged me last spring to adapt this lesson for more culturally responsive teaching, and my adapted lesson (with tracked changes from the original) is displayed below. I taught this adapted lesson several days after my students initially learned about American Indian removal. The original Native Knowledge 360 lesson requires students to read and analyze a contemporary case study of forced removal. My adaptation primarily focuses on making this lesson portion more relevant for my specific students by incorporating case studies that are happening right here in Memphis. The examples that I selected for the purposes of the lesson were immigration, gentrification, and municipal school districting/charter schools. I felt that these examples would be at least somewhat familiar to my students, while also providing ample room for them to think, write and speak about these topics.

A key question in this adapted lesson plan is, "What does removal look like today? What forces created American Indian removal?

What other forces could create conditions in which people have to leave their homes?" In order to connect the contemporary issues to our prior study of American Indian removal, my students completed a homework assignment on Google Classroom the night immediately prior to this lesson where they reflected in writing on American Indian Removal and its impact on American Indian people. They sought through the informal writing to explain what it means to remove American Indian people, and which forces contributed to their removal. Below are two student samples that were retained in my Google Drive over the summer. These samples are important evidence of my students' abilities to write about real-world problems; despite this issue being a historical one, considering and writing about it prepares my students to engage with more contemporary examples of removal.

In the first sample, which received a proficient grade, the student cites material learned through a dictionary search and through the Smithsonian 360 module to explain what it means to remove a people. He describes some contributing factors to American Indian removal, and astutely compares American Indian removal to a genocide, though he does not yet have that vocabulary word in his repertoire. This student is thinking and writing about real-world problems by describing the contributing factors to removal, making connections to other genocidal events in history, and applying a value-judgment to the event he has studied - that he believes it was wrong, and should not happen again.

The second sample scored below average, because it does not include cited sources from the Native 360 module or elsewhere, but I include it as the student still identifies some impacts of removal - that people had to give up their way of life, that others died, and that the government did not keep its promises to help them even after they signed treaties. A key takeaway here is that this student, too, writes that removal "was not fair." Though she has some work to do to more fully internalize the impact of a forced removal, the response indicates that she is considering and trying to grapple with the issue.

After ensuring in our bellwork discussion of the homework that my students had a working definition of removal, like those in the responses below, we moved on to working through the lesson (above) and addressing real-world issues of contemporary removal in earnest.

Lesson Texts & Written Responses

Module Texts & Discussions

The first set of texts for this lesson are built in to the Native Knowledge 360 lesson plan, and I used these in the guided portion of my lesson. You can view the texts by clicking to expand the slideshow to the left. A full version of this module is available by clicking here. We first worked together as a whole class to view the artifacts and read the article associated with the "High Tide Story." These artifacts provide information about the Guna people of Panama, who are forced to leave their ancestral homeland due to sea level rise caused by environmental changes. As we moved through the different artifacts and texts, answering the questions verbally, I could tell by their responses that my students clearly saw how environmental factors were forcing the Guna people to leave their home. This discussion is outlined in the slideshow. Then, my students worked with partners through the second set of artifacts called "Reza's Story," which are also outlined in the slideshow.

Material provided by the Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian

Written Response Sample

After completing the High Tide module via whole-class discussion, and as they worked through Reza's Story with their peer partner, students answered the Reza's Story question set in writing. The sample below depicts sample responses to the Native Knowledge 360 questions. In her responses, the student demonstrates that she is beginning to think about real-world problems when she highlights some of the challenges Reza could have faced on his journey, what she she would pack if she were faced with such a journey, and how a child in Reza's situation might feel. She also discusses the danger of Reza's situation by acknowledging that people would not travel so far with children unless they really needed to do so. These written responses help the student articulate her initial reactions and observations to the module, as well as to synthesize this new information with her background knowledge of inequity, removal, and justice from prior lessons and mini-units, such as our work on studying global poverty.

The questions from the module that she answers below are as follows:

Map

1. Approximately how many miles did Reza travel during his journey?

2. What countries might Reza have traveled through on his journey to Passau, Germany?

3. Approximately how long would it take to drive the distance from Herat, Afghanistan, to Passau, Germany? Why might Reza’s journey have taken much longer?

4. What might be difficult about traveling by rubber boat? Why?

Photograph

1. When you look at this photograph, who or what grabs your attention? Why?

2. Based on what you can see, predict the age range of the people in the photograph. Why might that be significant (important)?

3. If you were forced to leave your home forever and could bring only what would fit in a bag you could carry, what would you bring? Why?

Article

1. Who is Reza? (Describe what you know about him.)

2. What happened to Reza and his family?

3. When did Reza last see his parents?

4. What is/are the force(s) of removal in this story?

Quote

1. What is the tone (the emotion) of Kriegel’s statement?

2. Based on the quote, do you think children are leaving their homes by choice? Explain your reasoning.

3. Read the caption below the quote. Why do you think the children Kriegel works with may need psychological (mental health) support?

4. The journalist Katrin Bennhold interviewed Alois Kriegel as part of her story about migrant children. Why do you think Bennhold wanted to include Kriegel’s perspective?

Teacher-Created Module & Responses

Following our completion of the two case study modules provided by Native 360, we moved into independent pair work with three case studies that I designed and I pulled texts for myself. Students had the option to choose which case study they wanted to pursue based on my brief descriptions of the options. All of the options were specific to Memphis. I tasked the students with working to investigate a map and image that accompanied a reading article that they were to take turns reading aloud with each other. As my students read, they annotated the article, but saved questions and thoughts until the end. Then, the students answered thinking questions for their case study.

The texts I pulled can be viewed in the slideshow to the left, but you can click on the slideshow to see larger versions and accompanying interpretations. Overall, I sought to pull texts that my students would find highly relevant and interesting, and that would spark deeper discussions based on the background knowledge of the three issues I selected: immigration, gentrification, and education (municipal schooling and charter schools).

As my students engaged with the Memphis-specific case studies, they were guided by a set of three questions for inquiry to direct their thinking about the map, the image, and the article. A fourth question required students to begin thinking about real-world solutions for the problems they identified from their reading of the texts.

The first two documents below are from students who worked on Case Study #3, which was municipal school districting and charter schools. The first student focuses more on school segregation, but both students write about the shift to charter schooling and the reasons for which students can be removed from charter schools. Both students demonstrate through their first three questions that they have a good understanding of the issue, but it is in their written reflection responses in question four that the students demonstrate that they can invent solutions to large-scale problems, with the first student suggesting that charter schools ought to adopt an open admission policy, and the second student adopting an approach that encourages public schools to better serve all students. The third document belongs to a student who worked on Case Study #2, Gentrification. Though this student does not enjoy writing to the same extent as Students 1 and 2, he does provide accurate written responses to the questions, identifies African Americans as the population most affected by gentrification, and suggests that new laws and reforms might be able to mitigate the issue. Each student cites specific evidence from their maps and readings.

Some students do note that they did not find anything surprising about the maps. This may be due to prior familiarity with issues like school choice, charter schools, and municipal zoning, which are actually issues that brought some of my students to Heritage Baptist Academy in the first place. This serves as an additional example of how I sought to choose springboard topics that my students have already seen on the news or have some familiarity with in order to create more critical thought and deeper discussion.

Student Presentations

While I wanted my students to have an opportunity to gather their thoughts in writing, and to discuss their ideas with their partners, I always like to create as many opportunities as possible in class to share our learning. Particularly when it comes to real-world issues that affect our communities, I feel that these are issues that are worth talking about on a larger scale. For those reasons, I decided to have student pairs present their learning and some reactions to the class. As you may notice in the videos below, students vary in the information they share and how passionate they got in their presentations of the issue. Some students required more prompting than others. However, thinking and talking about issues surround gentrification, schools and immigration are present throughout. Most importantly, students are learning to use platforms where they have an opportunity to speak out to effectively inform others about community issues. This ability to speak on challenges and problems, and identify potential setbacks and solutions (as some students do in the videos that follow) is yet another tool in the global citizen's toolkit. As students practice utilizing this tool, they take their first steps in speaking truth to power - a skill that I hope will serve them and others now and into the future.

Through his speaking in this presentation, the student demonstrates his thoughts on one of the more complex topics we explored, which was gentrification. The student begins by giving us a running definition of gentrification. He defines it as landlords and property owners essentially selling to wealthier people without regard for the poorer tenants and residents currently living there. He goes on to explain that landlords might "hike up" rent, forcing less wealthy people to need to leave. He notes that people in our community are currently protesting against gentrification, as well as contacting local representatives to air concerns. The student offers as a solution possibly starting petitions to prevent gentrification, but this obviously needs to be fleshed out more. I push him on this later by asking if there are any more effective changes we could implement to mitigate gentrification and we discussed other possible solutions, like getting our local representatives on board.

Overall, this student demonstrates a firm grasp of what gentrification is, and what people in our community are doing to mitigate its effects. By sharing his findings with the class, we all get to learn about a process that affects our neighbors.

In this final sample, the students are grappling with the broad issues Shelby County Schools, which encompasses Memphis city schools since a merger about five years ago, are facing. They demonstrate thinking and speaking about real-world problems when they identify charter schools growth as a controversial issue in our city. While this group speaks in broader terms than the more detailed analyses presented in the previous samples, their major concern is the ability of charter schools to accept and reject certain students, sometimes based on academic and behavioral history. They posit that public school performance can get worse when students who are seen as "better" than average are removed to charter schools. I particularly like hearing the students in this sample talk through their solution, because they say that no one in Memphis is really working on this, so they had to create their own solution. This pair describes having charter schools shift to open enrollment. This ability to consider a real-world issue, and then posit solutions demonstrates that my students can think deeply about the problems facing our communities, and research the best ways to solve them.

I really like this second sample, because the student gets really passionate in his speaking on this issue. Before engaging in the assignment with his partner, who has a parent that has recently immigrated, he did not seem all that interested. However, after having a chance to talk to her and hear what her family's experience has been like in Memphis, he was able to internalize how poor treatment of immigrants can affect the people he cares about, like his friend and classmate. So my student does deliver a pretty fiery speech, but this is the power of communicating about real-world issues. By talking about the problems that challenge our communities, we gain greater understandings than before, and can work in partnerships with others to understand their perspectives, and mitigate or solve even the largest problems.

The student specifies that immigration is a problem that affects Memphis, and he narrows in on deportations and child separations, which have affected people in our direct community. In discussing child separations, the student demonstrates a high-level understanding of the process by outlining how adults are sent to separate detention centers before going in front of a judge, where 93% are then deported. I was particularly impressed with how this student cited a statistic from his prior reading and applied it to his analysis of the problems immigrants face. He goes on to explain that many parents are never reunited with their children.

Action Plans

Overview

Since my students did seem quite interested overall in studying some of the problems surrounding removal that are specific to Memphis, I decided to extend this thinking into an application project. Every year in the spring, I talk with my students about engaging in action to solve community problems. We talked through many examples in our community, but one example I always bring to the table is the TakeEmDown 901 movement, which was a successful, grassroots-led effort in Memphis to remove Confederate statues from our city parks. During the course of discussing this event, I prompt my students to identify what the activists did to have the city remove the statues. Once students had a running idea of the process, from identifying a problem to planning an action to solve it, I gave them a handout (pictured below) with three basic steps for creating a change. We talked about how creating change requires us to notice problems in our community, and then to determine what resources exist that could mitigate the problem. Students, who had followed the TakeEmDown 901 story on the news and in class, talk about how religious and community leaders did not like statues in our parks that do not represent us. With some prompting, individuals in the class were able to remember that the community and religious leaders reached out to organizations that could help them, such as the city council, C3 Citizens Cooperative, and Black Lives Matter Memphis. Then I asked the students what these people did to fix the problem, and my students talked at some length about how the leaders got the community to come out and demonstrate. They recruited speakers to give speeches and artists to make banners. They mobilized the college students and the young people to conduct walk-outs. They contacted the media and got a lot of coverage. I asked my students why they did all of those things, and one student was able to explain that their actions put a lot of pressure on the city council to have the statues removed.

The important takeaway from this discussion is that even grassroots-driven movements take planning and organization. By talking through the steps that a familiar movement took to create change, my students began to internalize what it means to take action, and how that actually looks, step-by-step, in the community.

Student Samples Overview

My school setting and culture makes it difficult to enact any community action that the parents would deem as too progressive or politically-oriented. As I was considering how to assess whether or not my students had actually learned about their ability to take collective and individual action in order to enact change through the culmination of these studies, I knew I would need to be creative, but sensitive to the restrictions of teaching and learning in a private, evangelical school. I decided that instead of initiating some kind of class-wide action and risking offending my students' families beyond apology, I could have my students work with their original partner from the removal modules and readings to design a theoretical action proposal for a class assessment grade. Whether or not they actually chose to follow through with the action is something that I left open-ended.

This assignment, for which the accompanying handout is included below, is designed to have students continue thinking and writing about real-world issues, and it comes with the added benefit of training students to navigate and challenge systemic injustice and inequity. I like to envision my students build a citizen-activist toolkit through their time in my class, where they leave with the ability to recognize instances injustice and inequity within their community, and can then select from their "toolkit" understandings and skills to help them address those instances.

The writing samples in the attached document below demonstrate, in addition to their ability to use evidence and texts to write about real world-problems, that my students are well-equipped with tools that they can use to challenge injustice. The community action proposals require them to think through the steps of taking action to mitigate a problem they identified from studying forced removal in Memphis. They worked in pairs to think through and determine courses of action, and then they designed artifacts such as letters to community leaders and fundraising posters that they could then potentially actually send or post publicly.

Gentrification Action Proposal

In the first action proposal (pages 1-3 above), the students demonstrate their ability to think and write about real-world problems by first explaining why gentrification is a bad thing (as it causes "poor people...[to] get priced out of the neighborhood") . Then, they identify people and organizations that they could work in partnership with to solve the problem, such as a city council member and the Memphis 3.0 movement. They have identified these community assets through online research, which is further evidence of the level of critical thinking that it requires to match community stakeholders to the problem of gentrification. Finally, they propose a plan: they will work with a Memphis city council member to form neighborhood boards to discuss community encroachment. This third step of the assignment is key, because this is where the transition happens from merely thinking, speaking or writing about a problem, and actually challenging the problem. As students went on to create their artifact, which in the first sample is a letter to the city council member, they develop a key awareness regarding their power to act. They came up with this action plan on their own, and, given that they have already written the letter, my students came to realize that they could very well send that letter and get started on mitigating gentrification in our community.

Immigration Action Proposal

In the second action proposal (pages 4-6 above), the students demonstrate their ability to think and write about real-world problems by listing some specific challenges that immigrants in our community face. They say that it is hard for newly immigrated people to find jobs, and that they sometimes need help for basic necessities. In the second step, the students make an important distinction during their thinking and writing process. They identify Mariposa's Collective as one organization that is helping new immigrants in Memphis. The students discuss two actions that Mariposa's Collective is involved in: mobilizing to disrupt ICE raids, and collecting and distributing food and basic supplies to immigrants living in and traversing through Memphis. My students admit that while they are not likely as middle school students to mobilize against ICE raids, something they can do is collect goods and ask others to collect goods to donate via Mariposa's Collective. A very important skill for community leaders, activists, and citizens is to know our limits. Through this distinction, my students demonstrate that they are thinking about how to mobilize in a way that is doable and reasonable for themselves given their ages, skills, and abilities. For their artifact on page 6, this pair have designed a flier that can be posted around town, passed out, or placed under windshield wipers in parking lots. The flier tells the public everything they need to know in order to help immigrants through an organization they may not have previously been aware of. Just like the gentrification group, this pair of students realized through the action proposal project that taking action can sometimes be simple. It can be as simple as creating a flier and spreading awareness. This is a key understanding that I hope my students will remember when they see instances of injustice and inequity in the future - that taking action does not have to be anything grand or disruptive, but taking action in some capacity is always the right thing to do.

Shelby County Schools Action Proposal

In the final action proposal (pages 8-10 above), students demonstrate their ability to think and write about real-world problems by expanding the more generalized statements they made in their video. I think this sample demonstrates that the students have gained a greater comprehension of education issues in Memphis, because rather than narrowing in on charter schools "only" accepting students with "straight A's" and good behavior, they have traced our education problems all the way back to desegregation and white flight. This demonstrates a quite nuanced understanding of the history of our education issues. They also demonstrate a level of self-awareness regarding how our own school, as a private school that was originally opened in the 1970's, could be a contributor to the problem. I really love the students' actual proposal here, because it demonstrates a real community partnership and it demonstrates that they understand the need to view community stakeholders as assets, not the source of the problem. They demonstrate these understandings by proposing that they work with schools to identify each school's specialty, or in other words, what sets that school apart. They want to shift our school opt-in programs to complete open-choice, and educate parents and students about the different specialties of the schools. That way, parents may send their children to schools that best suit their interests. On their attachment, which is a flier that could be handed out to parents, my students even show that they have researched some different high schools (and several that suffer from negative reputations in our city) and identify potential assets. All of this evidence demonstrates a key understanding that the students in this pair gained - that working collectively with the community to challenge inequity is a great way to mobilize and solve things, and that oftentimes, the solutions to our most difficult problems already exist in our communities.

Conclusion

This mini-unit, conceptualized based on a very specific module provided by the Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian, broadened and transformed my students' knowledge of equity, justice, and activism more than I would have ever imagined. By using a historic event as our entry point into contemporary comparisons of instances where removal still happens, and by investigating removal in our own local community, my class had ample opportunity to think, write, and speak about real-world problems. They were able to tap into their critical reading and critical thinking skills to approach the problems surrounding gentrification, immigration, and education from many different directions. Ultimately, my students demonstrated that they could synthesize their learning and new understandings by furthering their research of a Memphis-specific topic, and they internalize that they possess the ability to take collective action to challenge inequity and injustice. These are the classroom moments that reinforce for me that we are meeting my big goal to form students into active, global citizens. By building their toolkit of citizen-activist understandings and skills, my students are well-prepared to meet the challenges present in our community and in our world.

References:

Bump, Phillip. 2017. Where America’s undocumented immigrant population lives. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/politics/wp/2017/02/09/where-americas-undocumented-immigrant-population-lives/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.020d22e750ca

Equity Perspective. (2015). THE GLASS CEILING OF EQUITY FOR MEMPHIS CITY SCHOOLS. Memphis Merger. Retrieved from https://sociologyofsystems.wordpress.com/tag/white-flight/

Kedebe, L. F. (2018). University of Memphis runs the most segregated elementary school in the city. Will its middle school be more diverse? Chalkbeat. Retrieved from https://chalkbeat.org/posts/tn/2018/11/07/university-of-memphis-runs-an-elementary-school-with-most-affluent-white-students-in-the-city-leaders-want-their-new-school-to-be-diverse/

Native Knowledge 360. (n.d.). American Indian Removal: What Does It Mean to Remove a

People. p. 27-32. Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. Retrieved from https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360/removal/pdf/lesson-0-full.pdf

Sandifer, J. D. (2018). The organizer plans to sue the city for $10 billion for decades of disinvestment. MLK50. Retrieved from https://mlk50.com/protest-targets-gentrification-memphis-3-0-development-plan-e0c5afff9131

Shelby County Schools. (2018). SCS-Authorized Charter Schools

Annual Report. Memphis, TN: Shelby County Schools. Retrieved from http://www.scsk12.org/charter/files/2018/2018-CHARTER-REPORT.pdf

Smith, Maya. (2018). "There Is No Line": The Troubled State of Our Immigrant Community. Memphis Flyer. Retrieved from https://www.memphisflyer.com/memphis/there-is-no-line-the-troubled-state-of-our-immigrant-community/Content?oid=15820247

Smith, Maya. (2019). Report: Memphis Sees Gentrification Without Displacement. Memphis Flyer. Retrieved from https://www.memphisflyer.com/NewsBlog/archives/2019/03/28/report-memphis-sees-gentrification-without-displacement

Smithsonian Institute. (2019). AMERICAN INDIAN REMOVAL What Does It Mean to Remove a People? Smithsonian Institute NK360. Retrieved from https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360/removal/index.cshtml#titlePage